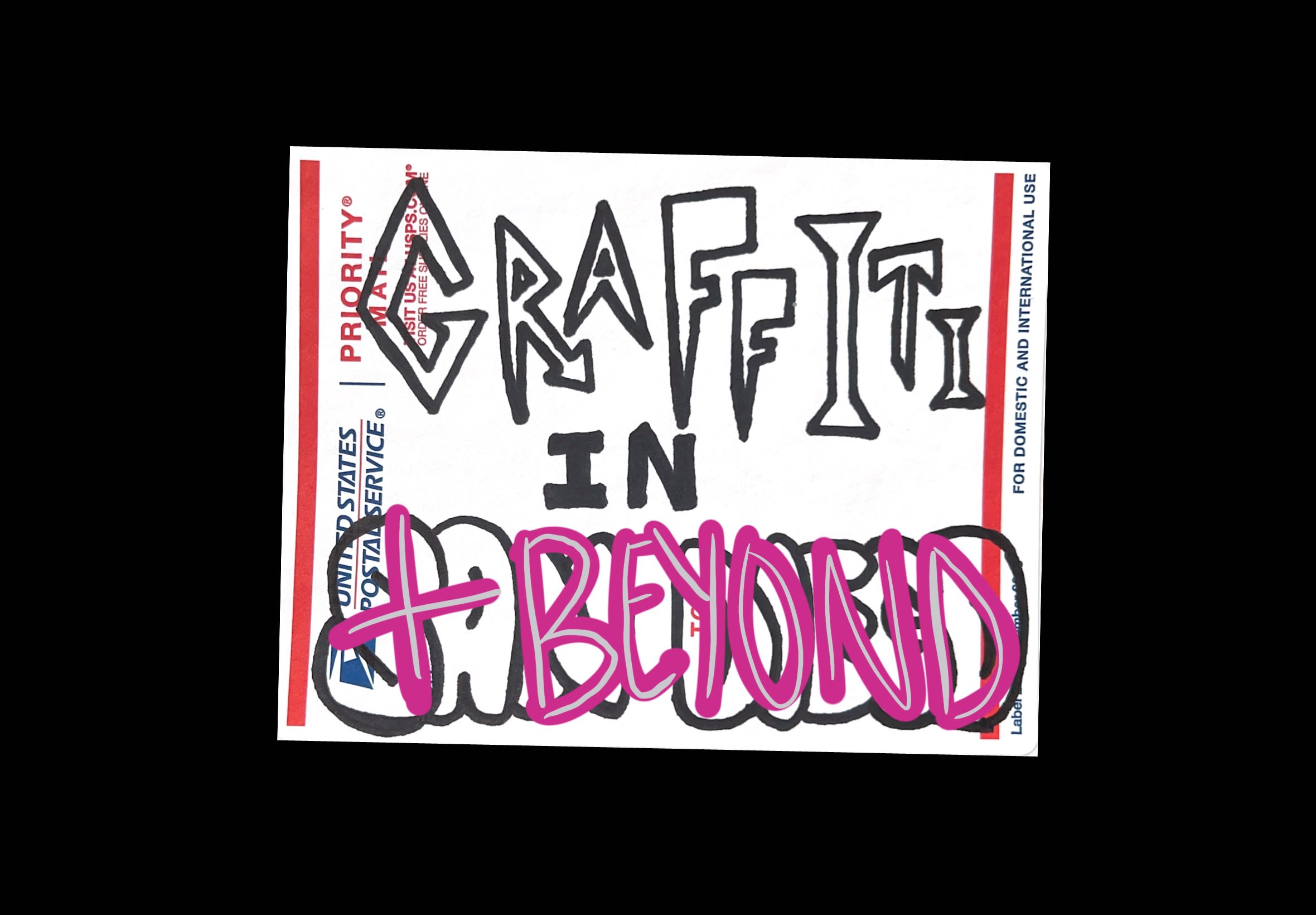

Graffiti in 'America's Finest City'

A central component to graffiti is its illegality. When the illegal aspect is taken away, it’s no longer classified as such.

Cities across the United States and beyond have had to either embrace the creativity through letting it run its course, launch a concerted effort to remove it, or succumb to the sheer volume and fight the winnable battles.

San Diego has chosen option B: to bring out “the buff man.”

Since the 2016 launch of San Diego’s “Get it Done” program, residents have been able to report issues from flooding to fallen branches within their neighborhoods directly to the City through an app.

In 2024 there were 47,891 requests for graffiti removal across San Diego through the “Get it Done” program. According to the San Diego Union Tribune, records from the city in 2021 showed expenditures of $300,000 toward the Urban Corps program, another $800,000 annually on San Diego’s in-house graffiti crew which handles tags on public property, and $250,000 on two code compliance officers who address graffiti on commercial property.

Certain enclaves within the downtown region maintain their own effort toward keeping it clean. Business organizations like Little Italy Association of San Diego and North Park Main Street employ their own graffiti removal request service.

Freddie Carruthers has worked in graffiti removal with the North Park Property and Business Improvement District for 16 years, and serves as the maintenance manager now. Per month they remove anywhere from 400 to 1,000 tags - mostly illegible scribbles, he said.

“I have matching paint for almost every single business in North Park,” Carruther said.

North Park’s program has been around for almost 40 years. In the past decades, they have ramped up their operation to become a full-time endeavor, which he said lends itself to the fact that North Park has become a more upscale area.

“Within six hours of it being reported it’s coming down.”

In order for elaborate throws to stay up, they have to stay hidden. Jason Gould, the owner of Visual, a shop and gallery in North Park dedicated to urban art, said that this inevitably pushes an already underground scene, further into the shadows.

However, it doesn’t have to hide online. It’s immortalized. It’s commonplace in the digital age for writers, those who put up tags and throws, to share their work online. They can connect with others in the area that want to put pieces up, possibly be picked up by a crew and expand the reach of their art further than their city.

Uncovered: Women in San Diego's scene

When ShePosse began sharing her graffiti on the internet, posting photos of her paste-ups and stickers scattered throughout San Diego and Solana Beach, she encountered the world of stickers through discord channels. It was there in those chat rooms, before she settled on a name, that it struck her. With every “dude,” “brother” and “man” that would be used in reference to her, the assumption took shape: men were behind the writing on the walls.

Graffiti is an undeniably male-dominated space. But, women have always been in it. After all, a large part of the practice is anonymity.

“It is a very Alpha oriented, macho kind of endeavor,” Gould said. “I mean over the years, we have seen there's way more female interaction in it. And, there was always some there in the first place. But it would be hard to say, because I don't think historically, like it's been covered or documented.”

Invasive Animal puts up wheat paste around downtown San Diego and would rather not to correct assumptions around her identity. It’s amusing to her when DMs to her account are addressed to a man. She laughs at the thought with the giddy of a child trying on costumes.

PondboyTags started drawing their character Pondboy, a mouse wearing a baseball cap, during their senior year of high school. When she came to college in San Diego, she found herself amongst other taggers and inevitably fell into the scene.

Eventually she crossed paths with artists like Distant Peace and WhaleBomb, who have risen within the ranks of San Diego’s graff scene as recognizable artists. She ended up collaborating with them and offering up her characters to be a part of a zine they created called “Tag Magazine.” That project is one of her favorites, she recalled with an undeniable smile bursting between her lips.

But, her entrance onto the scene didn’t immediately offer up a community.

“I remember when I first was getting into graffiti, there were some people I was around who would constantly put me down and say I wasn't good enough and make me feel really bad for just being a beginner,” they said.

“Presenting as a woman in any space, really, you get looked down on a lot. I get talked to like, I don't know what I'm doing. And, hey, sometimes I don't, but that doesn't mean you need to give me sass about it. It just, it feels strange. I feel like an intruder, I've been here for years. I know so many people, so many great friends, and I still feel like I don't belong somehow.”

ShePosse was born out of the desire to find the other women putting their work out onto the streets. The name, an homage to her graffiti hero, Shepard Fairey and his infamous “Andre the Giant has a Posse” sticker, was her way of saying, “Where are the women? Where is my ‘she posse?’”

Tools to change: 228 labels, spray paint, pasco pens

In studying the potential of graffiti as a tool for education Richard S. Christen, a professor at the University of Portland, highlighted in the article “Hip Hop Learning: Graffiti as an Educator of Urban Teenagers” that despite not every piece having overtly political messaging the act of writing itself is political.

“Perhaps graffiti's most significant educational contribution is that, unlike most schools, it introduces writers to a critical understanding of these power structures and involves them in the construction of alternatives.”

Christen argues that overtime, writers engage in a reform process that educates them and, to a certain extent, can provide them with the tools to change their individual and collective lives.

As PondboyTags started to examine the art they made through graffiti and the characters they adopted to tell stories on the streets, realizations emerged.

“That was also a doorway for me to think about how I saw myself,” they said.

“Kind of like, ‘Why am I drawing myself as a little boy, like a little cat guy when I grew up, like as a girl?” So that kind of started to open a door into gender and what that meant to me. Because all of my characters, without a doubt, have always been male, and I don't know why, then I kind of figured out, okay, that might mean something, and started thinking about who I am as a person, what I experience and having Klaus the cat go through that too.”

In their daily life, PondboyTags, is pursuing a career in visual art. For her, writing graff and constructing characters is a way to release creativity in a more vibrant, playful way as the other work she produces are large scale paintings depicting representations of weighty topics inspired by Catholic relics and culture.

Invasive Animal is no stranger to the world of gallery work as well. She entered the world of graffiti, she said, to escape ego. Tired of needing someone’s approval to have a space to showcase art.

While PondboyTags remains firm on the fact that there are some “crazy ego problems” within the graffiti community, Invasive Animal finds it to be one of the few places where her art is free from it. No one needs to be good enough to put something up on the street. Anyone can tag next to a Banksy.

“I feel it’s very liberating to be anonymous,” Invasive Animal said.

“Here and there people know who I am, but it’s just not the same. It’s just about what you put down and not anything else, but if people like what you put on the streets. So it’s really, I think, merit based or at least people-pleasing-based rather than who you know or who gave you this connection.”

ShePosse didn’t get into petty crime in order to achieve recognition, yet she has. She's contributed to an all-female show at Fairey's Subliminal Projects. Her art which usually belongs on alley walls, has found itself in gallery halls from New York to Portland.

"It’s weird being asked to be a part of galleries, like really you want me? Are you serious?"

Nor did she set out to empower women, it came second. In the beginning it was just about the stickers brought her, and in many ways it still is.

“Colors are what make my heart sing. So it's just a matter of, like, sitting down and starting and seeing what and I just naturally, you know, gravitate to drawing women for multiple reasons, just to represent women, to put us in the forefront. I'm not putting myself in a box. It's really my therapy because I have a lot of other practical things going on.”

ShePosse was born and raised in New York City, she went West to get sober. She is 19 years clean. To make it this far, she said she has had to find the root cause of her pain, to really sift through why she didn’t want to be alive.

For her, the act of creation is a way to make sense of the noise. To filter out her feelings, to be able to look them in the eye. When she makes her mark around the beach town she calls home, driving down dead ends drives and stopping by streets that lead to corporate parks, it’s evidence of her being. Her ability to transform electrical boxes into canvas and curbside signs into a collage reflects a different woman than she grew up knowing. Like the paste-up she made two years ago, she looks back and wonders who that girl was. She’s been buffed down to her bones and pasted over with neon renewal.