Setting the Scene

333 years of Spanish rule.

48 years of American rule.

In 1946, the Philippines began its journey to healing after 381 years of colonial rule.

The relationship between the Philippines and the United States (U.S.) has been jaded from the very start, highlighting America’s imperial past and uneven economic relationship between the two countries and their peoples. In 1898, the U.S. acquired the Philippines from Spain after signing the Treaty of Paris, on December 21 of that year the U.S. government declared military rule in the Philippines.

The Filipino people had just successfully led a rebellion against the Spanish, winning back their rightful independence. The taking of the islands by the Americans cost Filipinos their sovereignty once again.

Anthony Ocampo, author of The Latinos of Asia : How Filipino Americans Break the Rules of Race describes the damage the war left; “It is estimated that anywhere between four hundred thousand to more than a million Filipinos died as a result of the conflict, prompting some historians to dub the bloody Philippine-American War as “the First Vietnam,” (Ocampo 9).

American colonial rule lasted for 48 years. It wasn’t until 1946 that Philippine independence was recognized by the U.S.

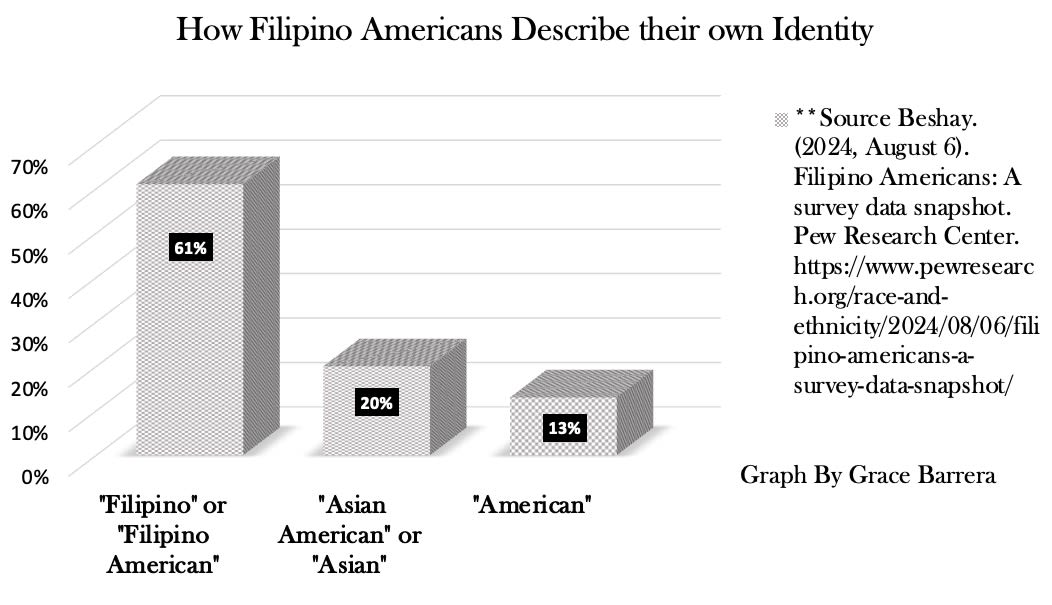

The Philippines becoming a sovereign nation, did not excuse the land from the U.S. neocolonial influence displayed through the continued military, economic and cultural presence in the country. The four long centuries of Western colonial influence in the Philippines has since impacted the modern-day Philippine society and Filipino-Americans living in America today.

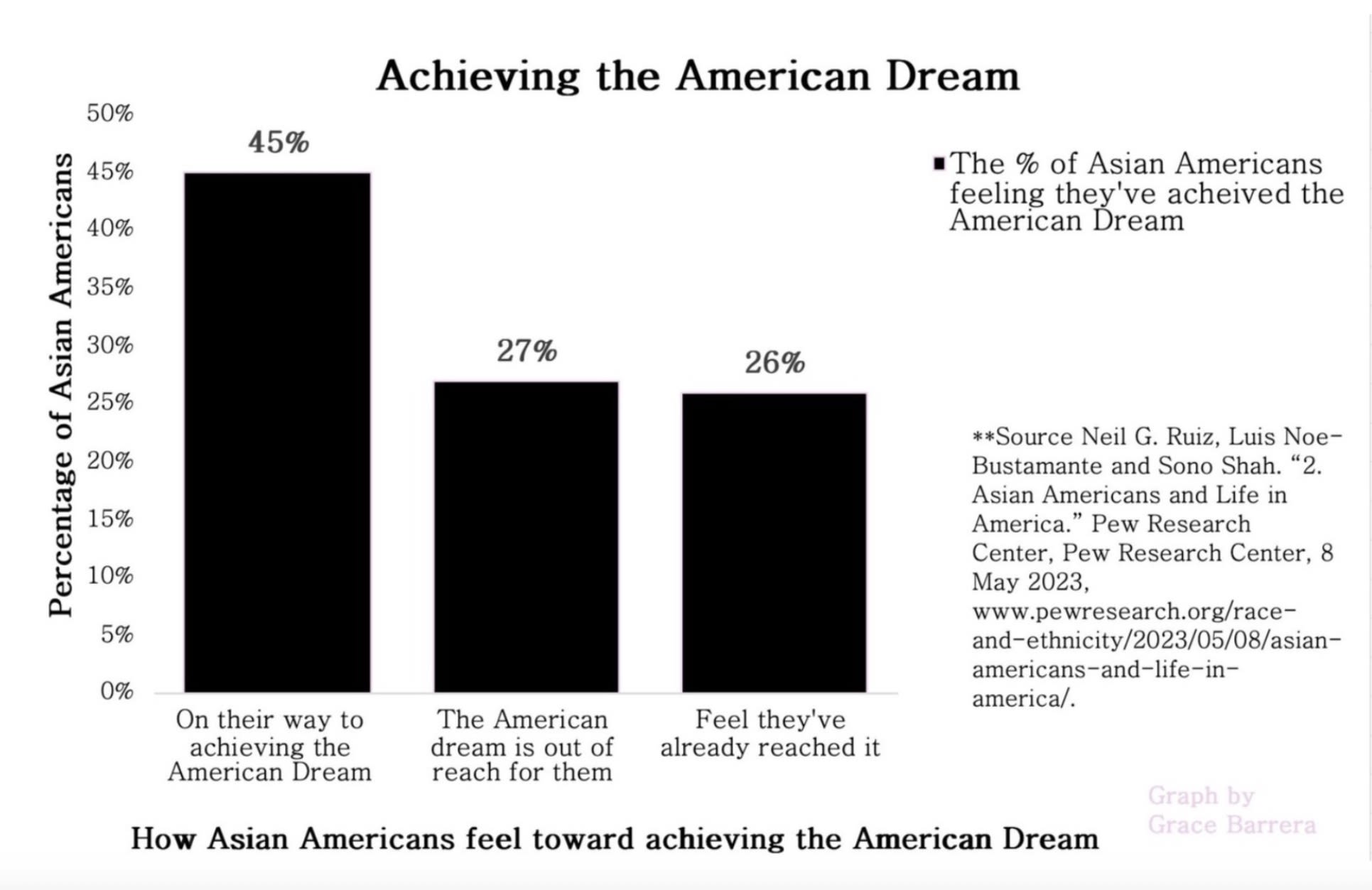

“The American Dream”

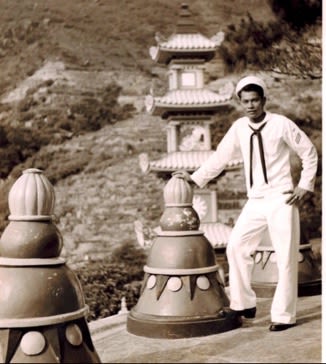

Lured by the dream of America, over 35,000 Filipino nationals enlisted into the U.S. Navy, promised to earn U.S. citizenship through enlistment. The American dream and life was broadcasted to Filipinos as the ideal life, urging thousands of Filipino men and women to hop on that opportunity as fast as they could.

In Jose Antonio Vargas' documentary, “Documented,” where he shares his journey from the Philippines as a undocumented immigrant, Vargas says “America seemed inevitable,” while growing up in the homeland.

For Filipinos growing up in the Philippines during the 20th century, this feeling reigns true, as the influence of America has engrossed the country for over 100 years, America is inevitable for many Filipinos.

The U.S. Navy and Filipinos

The U.S. Navy had a labor problem and Filipino recruitment was their solution. Former colonies and villages in the Philippines became U.S. military installations; Sangley Point in Cavite City being one of the central recruiting stations for Filipinos, the same naval base my grandfather, Jose Fernandez Barrera was deployed from.

Yen Le Espiritu, sociologist and author of Home Bound:Filipino American Lives Across Cultures, Communities, and Countries writes in her book, “While Filipinos from any region could and did apply to the U.S. Navy, those from these two provinces [Cavite and Zambales] had a distinct advantage. Living near the recruiting stations, these Filipinos benefited from their firsthand contacts with U.S. naval personnel”(Espiritu 106).

My grandfather’s hometown of Cavite regularly conducted seminars by Filipino enlistees on how to join the U.S. Navy. I’m not exactly sure what pushed my grandfather to enlist, whether it being his older brothers who were already enlisted or the influence the U.S. Navy had in the town he was brought up in. But I do know that he viewed America as a place of opportunity.

Vehement believers in the American dream, many young Filipino men who were already facing poverty, enlisted in the U.S. Navy to start a new life. Majority of the Filipinos worked on the ships as cooks/stewards, rarely promoted to higher positions. For many Filipinos, the shoe-in of their race to fill the entry level positions was humiliating and they felt they weren’t looked at with the same respect as their white counterparts.

“Even as late as 1970, 80 percent of the Filipinos in the U.S. Navy were in the steward rating. It was this shared “location” within the U.S. Navy– that of a “brown skinned servant force” –that compelled Filipino Navy personnel to expand their social frame of reference and adopt an all-Filipino identity. In other words, it was through their racialized class experiences, especially the realization of a racial caste system in the Navy, that an all-Filipino identity was made.”(Espiritu 107).

Going to California

For my grandparents, Jose Fernandez Barrera and Betty Carbajal Barrera, they took advantage of the American dream and the opportunity to start a completely new life away from home. Set to create a home in a new place. I believe they did not grow up thinking America was inevitable but instead they grew up viewing the opportunities of America to be a blessing.

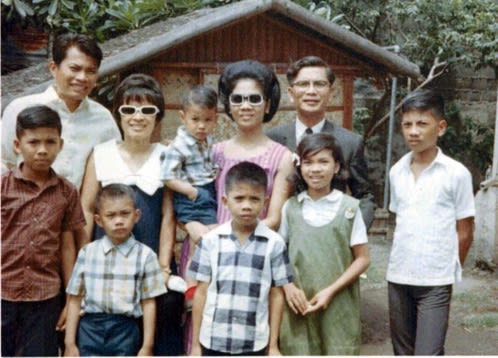

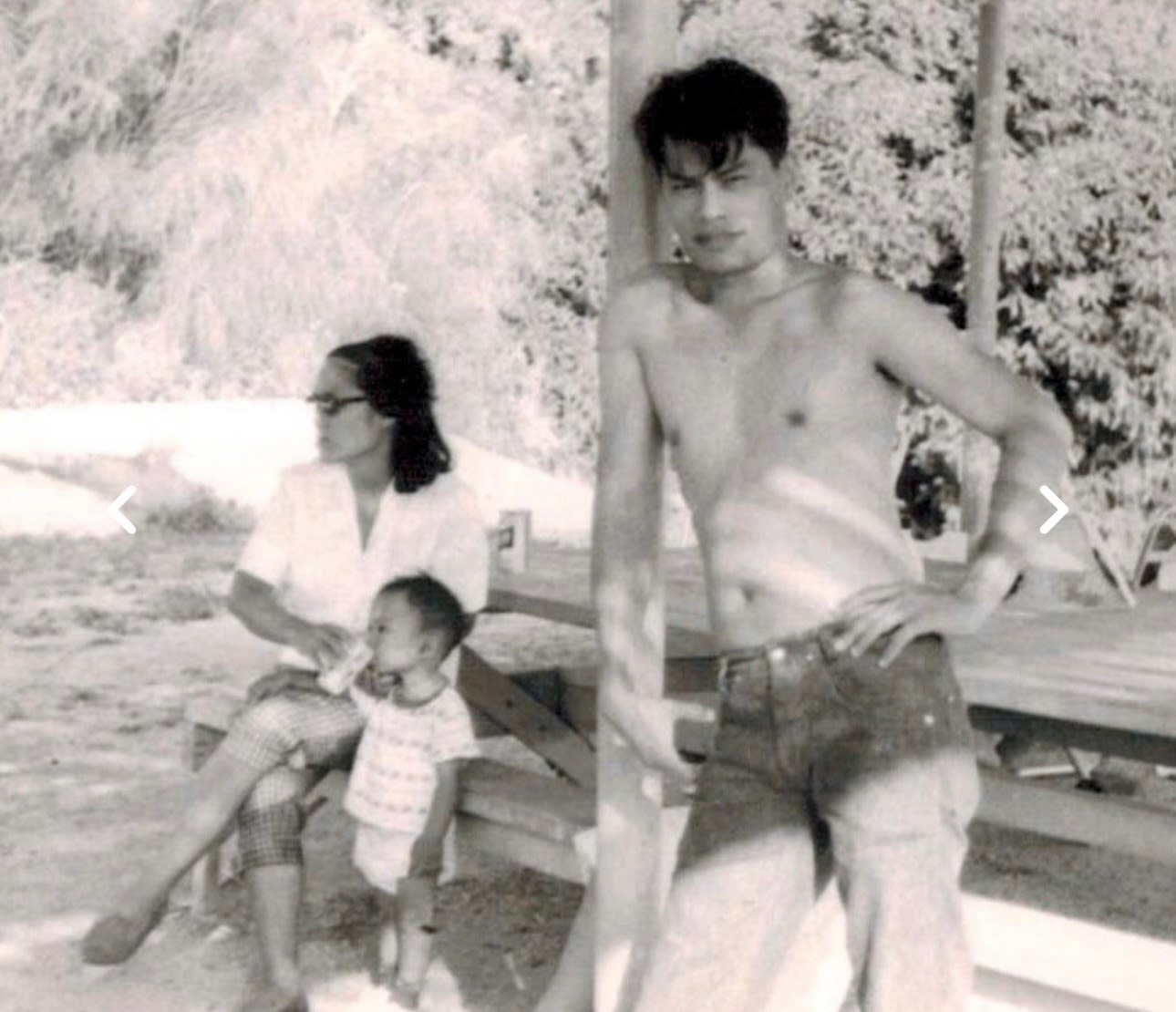

They were both 22 when they arrived in America, coming from two completely different parts of the Philippines. My Grandpa Joe grew up in Cavite City, a naval base town near the country’s capital, Manila, while my Grandma Betty grew up 10 hours away in Ilocos Norte, now a tourist destination, known for its white sand beaches.

When my Grandpa came to America, he took it as a chance to change his life and the lives of those who would come after him. Growing up in a family with nine other siblings and elderly parents, my grandfather was determined to set a new path for his brothers and sisters.

For my Grandpa and for many others who come to America, America meant opportunity but it also meant sacrifice. In order to live out the life he wanted, he had to leave behind parts of his Filipino culture for the American dream. Moving to America and fitting in with Americans was a culture shock that my Grandfather fully embraced, from head to toe.

Hanging on my bed frame is one of my Grandpa Joe’s favorite hats. I got to take it the day we cleaned through his house after he passed. The hat is worn and stained. It has definitely seen countless days in the sun as the pearly white threading has now turned cream. The details comfort me; the red brim and green detailing, representing the state of California’s flag and of course, the California grizzly bear embroidered front and center. The hat reminds me of how much he loved being an American, a Californian and a San Diegan.

Miles traveled and risks taken, Betty and Jose both ended up in Glendale, California in the late 1960s. The blooming community of Filipinos in California fostered matchmaking and the two were set up on a blind date by their friends. From then on they began their new lives in California together.

When a group of Filipino nurses and Filipino Navy men come together, you are bound to see many marriages form.

My Grandma Betty was a nurse, ran a floral business and was my father’s best friend until she passed away when he was 20 years old and in dental school. He had to take a year off before graduating because it was all too much. I never knew my grandmother but the bits and pieces I do know, have become information I’ve clung onto tightly.

She was known to be the stricter parent and was a devout Seventh-Day Adventist, heavily involved at First Paradise Valley Seventh Day Adventist Church and the San Diego Filipino-American Seventh Day Adventist Church.

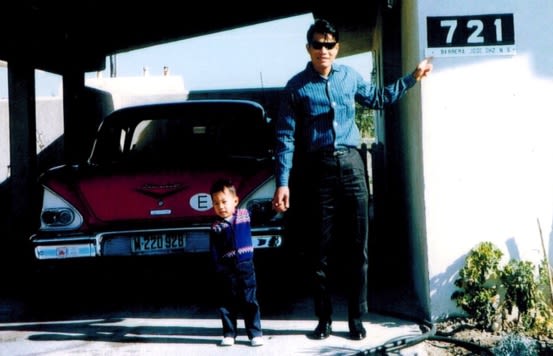

My Grandpa Joe served in the U.S. Navy, fought in Vietnam and Korea, was a businessman who ran motels, opened up a Swensen’s ice-cream shop near SDSU that unfortunately is now closed and committed his life to being a proud American.

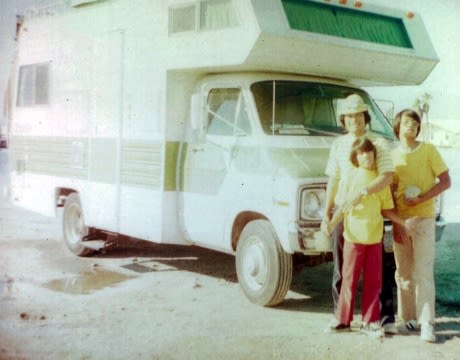

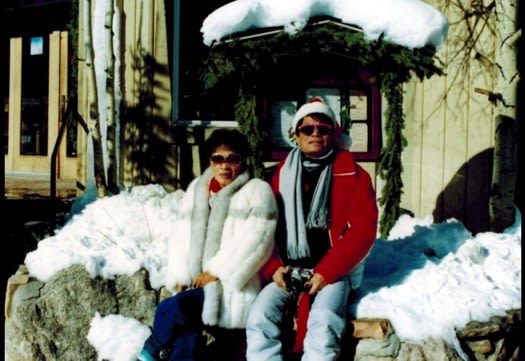

The two began a family and lived out their version of the American dream. They owned an RV, bought their dream cars, moved into a home both them and their friends adored in Bonita and took the occasional family trip to Big Bear during the winters.

My father describes his parents as people who worked for the American Dream.

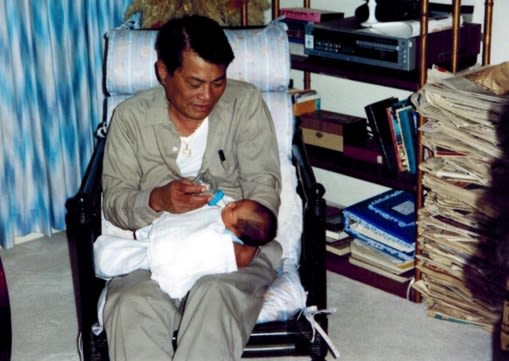

The final years of my Grandpa Joe’s life were spent on dialysis. My sister and I were able to visit him a couple weeks before he passed. He looked so different then, like his body had aged 10 more years since the last time I had seen him months prior.

The feeling like I never really knew him loomed over me when I was at his funeral in 2016. I was only 12 when he passed away but I remember wishing at the funeral that I asked him more questions. His funeral was crowded and an all weekend event, it was then that I noticed how loved he was. I hugged so many Aunties and Lolas, saw cousins I hadn’t seen in years and together we celebrated the life of my Grandpa Joe over lumpia and pancit.

The photos that filled the slideshow playing at the funeral service showed a colorful and dynamic side of my grandfather – smiling with hands in the sky. I look back on these photos and wish I got to know that person better.

For the part of my life he was alive, he was always giving me tight hugs and constantly repeating his statements twice with a thick Filipino accent.

He lived in Henderson, Nevada for a good amount of my childhood so I always associated him with Las Vegas, which isn’t too far off because he did really love to gamble. Whenever we would go to visit, by the end of the drive everyone was tired and overheated, but not for long. As soon as we saw Grandpa, he would light up and say “Come inside for halo-halo.”

The ice-cold treat, halo-halo which means "mix-mix" in Tagalog, is a mixture of crushed ice, ube ice cream, fruit jellies, sweetened beans and flan. The way you eat it, is by doing just that, mix mix.

I haven’t eaten it since he passed.

The majority of my Barrera relatives are buried at Glen Abbey Memorial in Bonita, only a 25 minute drive from the apartment I currently live in. I had never gone to visit since moving down to San Diego and my cousin CJ and I were the only Barrera’s in the area who could go and visit, so we went on My Grandpa's death date, April 5th. We probably should have checked what grave number he was buried at before going but we figured we’d eventually find it because of how many Barrera’s were buried there. We had been there for funerals and visits many times before but our memories served us horrendously.

We spent 30 minutes looking as sprinklers drenched us from top to bottom, we couldn’t even react to the water spraying at us because, well, we were at a cemetery. Coming to our senses, we both took turns calling our dads, who then added one of our uncle’s to the call. We ended up on Facetime in order to find the grave.

“Look for the smaller pole with the American flag and there should also be a water spigot there, go to the right of that and that’s where Grandpa Joe is buried. You’ll find it there… Did you find it?,” my uncle said over the phone.

The instructions he gave, led us straight to it and funny enough we had been right by the grave the entire time, dancing around it, in sync with the sprinklers.

My Grandpa Joe and Grandma Betty are buried together, side by side their headstones sit. I picked off the dead grass and overgrown roots while CJ filled up the vase with water from the spigot. Together we placed the flowers between them. We sat with them, sharing both silence and conversation, while our soaked clothes began to dry from the sun.

Here they lay, born in the Philippines and laid to rest in America, where they made home.

Sources

Paligutan, P. James. Lured by the American Dream : Filipino Servants in the U. S. Navy and Coast Guard, 1952-1970, University of Illinois Press, 2022. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/pointloma-ebooks/detail.action?docID=29405860.

Ocampo, Anthony Christian. The Latinos of Asia : How Filipino Americans Break the Rules of Race, Stanford University Press, 2016. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/pointloma-ebooks/detail.action?docID=4414775.

Espiritu, Yen Le. Home Bound: Filipino American Lives across Cultures, Communities, and Countries. University of California Press, 2003.

Beshay. (2024, August 6). Filipino Americans: A survey data snapshot. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/race-and-ethnicity/2024/08/06/filipino-americans-a-survey-data-snapshot/